Donate

| SECTION I | ---------------------------------- | GENERAL |

| SECTION II | ---------------------------------- | USE OF RADIOS |

131. General

Ideally, the successful execution of a patrol mission would require only that the detailed plan be carefully followed. In practice, however, this is not, enough. Many aspects of the patrol cannot be specifically planned; many situations arise which require revision or modification of carefully made plans; many actions and reactions are the result, not of specific planning, but of the skill, ingenuity, and aggressiveness of patrol members. The successful conduct of a patrol is the end result of the continuing efforts of every patrol member to earnestly apply his knowledge skills, and ingenuity to the accomplishment of the mission. This chapter explains principles to follow in the conduct of patrols and some of the techniques which may be used.

132. Control.

The success of a patrol depends on the control the leader is able to exercise over it. He must be able to maneuver his men as the situation requires; to start, shift, or stop their fires as needed.

a. Control by Voice and Other Audible Means.

(1) Oral orders are a good means of control.

Orders are spoken just loudly enough to be heard. They are shouted only in an emergency. At night, or when close to the enemy, subordinate leaders come forward, and orders and information are given in a low voice or whisper, or by silent signal If it is not appropriate for subordinate leaders to come forward, the patrol leader may move from man to man or may use a messenger.

(2) Radios are an excellent means of control especially in a large patrol, provided good radio discipline is maintained.

(3) Whistle signals are an excellent means of control when secrecy is not necessary as, for example, during enemy contact.

(4) Other sound signals can be used if they will serve the purpose intended. They must be natural sounds that are easily understood. Bird and animal calls are seldom suitable. They are difficult to imitate and their proper use requires detailed knowledge of the bird or animal imitated. A few simple signals are better than many signals. Sound signals must be rehearsed before starting on the patrol.

b. Silent Control Measures.

(1) Arm-and-hand signals can be used when appropriate, such as near the enemy. All members must know the signals and be alert to receive and pass them to other members. The patrol leader must be alert for signals from any patrol member. Patrol members may develop special signals of their own during training. Any such signals must be understood by all. Gestures may be appropriate when no established signal fits the situation. For example, compi11ed the hands to the eyes it is pointing in a certain direction can indicate a mnn is to observe in that direction.

(2) Infrared equipment such as the sniper scope, the infrared weapon sight, the meta scope, and infrared filters for the flash light may be used for sending and receiving signals and maintaining control at night.

(3) Luminous tape can be used to assist in control at night. Two strips, ½ inch by 1½ inches, ½-inch apart (about the size of a captain's bars), on the back of the cap or collar aid in following the man in front. Care must be taken to cover these when near tne enemy. The luminous marks on the compass may be used for simple signals over short distances.

c. Patrol Members Assist in Control.

(1) The assistant patrol leader, when positioned at or near the rear of the patrol, prevents men from falling behind or by getting out of position. He is alert for signals and orders and insures that other members receive and comply with them. when the patrol halts, he contacts the patrol leader for instructions.

(2) Other subordinate leaders move with and maintain control over their elements and teams. They, too, are alert for signals and orders and insure their men receive and comply with them.

(3) All patrol members assist in control by staying alert and passing signals and orders on to other members. A signal to halt may be given by any patrol member but the signal to resume movement is given only by the patrol leader.

d. Accounting for Personnel.

An important aspect of control is the accounting for personnel knowing all members are present. Personnel must be accounted for after crossing danger areas after enemy contact, and after halts.

(1) When moving in single file, the last man "sends up the count" by tapping the man in front of him and saying "one" in a low voice or whisper. This man taps the man in front of him and says "two." This continues until the count reaches the patrol leader. The men behind plus himself and the men he knows to be ahead, should equal the total of the patrol.

(2) The count is sent forward when the patrol leader turns to the man behind him and says "send up the count." This is passed back to the last man, who starts the count.

(3) Each man insures that the man he taps receives and passes on the count.

(4) In large patrols, or when moving in a formation other than single file, subordinate leaders check their men and report to the patrol leader. It may be necessary to halt the patrol to obtain an accurate count.

(5) Subordinate leaders automatically report, or the last man "sends up the count" after crossing danger areas, after enemy contact, and after halts.

133. Departure and Re-Entry of Friendly Areas

a. Movement must be cautious when approaching positions in friendly areas because all personnel are regarded as enemy until identified. The patrol is halted near the position, preferably where there 1s concealment and cover; the patrol leader contacts the position, and if possible, the local leader. He takes at least one man with him more if appropriate, remembering that unusual activity may attract enemy attention and endanger both the patrol and the position. The patrol leader requests the latest information of the enemy, terrain to the front, and known obstacles. He checks for communications facilities, fire support the position can provide or obtain, and any other assistance the position may be able to provide. He confirms the challenge and password and, if the patrol is to return through the position, he determines if the same men will be manning the position at that time. If not, he instructs them to be sure to notify their relief of the patrol's expected return. If other positions are to be contacted, he asks for a guide to the next position and requests the position be notified of his approach, if communications facilities permit. If mine fields or wire are to be passed he . ' re~uest~ a guide. If the patrol's initial rallying point is to be in the position's area this is coordinated.

b. Personnel in forward positions are given only the information needed to enable them to assist the patrol. This is usually limited to the size of the patrol, its general direction and whether it is to return to the position. If it is to return to the position, the expected time is also given. Mission and route are not normally given.

c. The same general procedure is followed in re-entering; friendly areas. Each position is given any information obtained by the patrol that may be of immediate value. If any patrol member is missing, each position is warned to be on the lookout.

134. Avoiding Discovery

a. All patrols, except search and attack patrols on target~of-opportunity missions, try to reach the ob1ective without being discovered. Contact with the enemy is avoided, if possible to reduce the possibility that mere knowledge of the patrol's presence may compromise the mission and to avoid the risk of losing men whose skills are vital to the mission.

b. Reconnaissance patrols also try to conduct their reconnaissance or surveillance without being discovered, In-formation may lose some or all of its value if the enemy knows we have it.

c. Patrols also avoid contact and discovery during return, unless the assigned mission includes engaging targets of opportunity during the return trip.

135. Navigation

a. The patrol leader assigns one or more men to be navigators for the patrol, checks them often, and changes them promptly if they do not navigate properly. The patrol leade1· is responsible, regardless of who is doing the job.

b. At least two men are assigned the pacers to check the distance from point to point. They are separated in the patrol so that they will not influence each other's count.

c. The route is divided into legs (para 127, and fig. 7'5). Pacers start their counts over at the beginning of each leg. This makes the pace count easiest to keep and provides periodic checks on the accuracy of the pacers.

d. The pace count is sent forward when the patrol leader turns to the man behind and says, "send up the pace." This is passed back to both pacers, each of whom sends up his pace count in meters; for example, "200," "one-seven-five," or "one-five-zero." The two counts will seldom be exactly the same; the average of the two counts is a good approximation of the distance traveled if both pacers are performing properly.

e. All men must understand that the counts of both pacers are to be sent forward. The patrol leader must know both counts in order to properly check on the pacers.

136. Actions at Danger Areas.

A patrol's actions at danger areas are essentially those of the individual soldier who must cross a danger area (para 28). The patrol leader specifically plans for danger areas he is able to identify in advance and makes general plans for crossing other danger areas the patrol may encounter.

The following are considered and applied as appropriate.

a. The near side and flanks of a danger area are reconnoitered first; then, the far side is investigated. After determining that the area is clear, the patrol crosses as a group if the danger area is small, such as a minor trail or the patrol crosses by small groups, each covering the other, if the area is large enough to cause more than brief exposure of the entire patrol.

b. Gaps in wire or minefields are avoided. They are usually covered by fire. The patrol makes its own gap and sends security through before passing.

c. When crossing a stream, the near bank is reconnoitered and the patrol positioned to cover the far bank while it is being reconnoitered. After the far bank is checked, the patrol crosses quickly as a group, or crosses in small groups, each covering the other when the stream is too deep for rapid crossing. When crossing requires swimming, improvised rafts are used to float weapons, ammunition, and equipment. In cold weather, clothing is also floated across.

d. When non-collapsible boats are used to cross a stream, they are returned to the starting side and hidden a short distance up or downstream from the crossing site. If discovered by the enemy, then they do not so clearly indicate the patrol's presence and its direction of movement. One or more men are left to conceal themselves nearby to protect the boats, if possible, or to provide early warning if they are discovered. On return, a different crossing site is used, if feasible.

137. Security.

Organization for movement provides the patrol some security, but not enough. Additional steps must be taken.

a. Day Patrols.

(1) The patrol is dispersed to the maximum consistent with control, visibility, and other factors.

(2) Areas of responsibility are assigned to the front, flanks, rear, and overhead. Security personnel are kept far enough out to furnish early warning to the patrol.

(3) Movement along high ground is cautious to avoid silhouetting the patrol on ridge lines.

(4) Exposed areas are avoided and maximum advantage taken of existing concealment and cover.

(5) An even pace is maintained. Rushing and running are avoided. Sudden movements attract attention.

(6) Known or suspected enemy locations, key terrain features, and built-up areas are avoided.

b. Night Patrols.

Techniques £or night patrols vary only slightly from day patrols, with the amount of variation depending largely on conditions of visibility.

(1) The patrol is dispersed less than in day.

(2) Quiet movement is more essential. Sounds 0arry farther than in day.

(3) Movement is slower to reduce danger of men becoming separated from the patrol.

c. Avoiding Ambush.

Proper security and reconnaissance are the best means to avoid ambush. The patrol must always be alert and suspicious of all areas. Certain areas are more suitable for an ambush than others. These areas roads and trails, narrow gullies, villages, and open areas-are approached with caution. Routes used by other patrols are avoided.

d. Halts.

(1) The patrol is halted occasionally to observe and listen for enemy activity.

This is a security halt. When the patrol leader signals, every man freezes in place, maintains absolute quiet, looks, and listens. This is done upon reaching a danger area and periodically during movement en route. The security halt is similar to the immediate action drill freeze, discussed in chapter 21. A security halt is appropriate just after departing friendly areas and just before re-entering. When concealment is scarce, men may be signaled to go down on one knee or to the prone position. Observation is not good from these positions, however, and the large body area in contact with the ground makes quiet more difficult to maintain. A security halt is brief; it is difficult for men to remain absolutely still and quiet for more than 2 or 3 minutes.

(2) The patrol may halt briefly to check direction, send out a reconnaissance party, send a message, eat, or rest. An area is selected which provides concealment and, if possible, provides cover and favors defense. All-round security is established. Care is taken to insure that everyone moves when the patrol starts again.

(3) If the patrol's halt is of more than brief duration, a patrol base is established (ch 23).

e. Security to the Front.

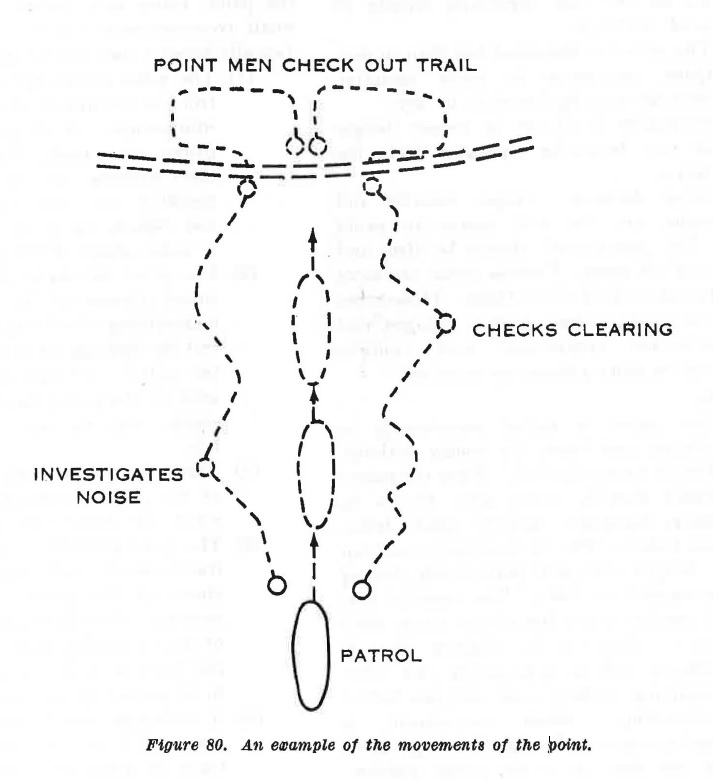

This is provided by the point, which may consist of one man in a small reconnaissance patrol. A combat patrol (usually larger) uses two or more men ( fig. 80). (1) The point moves well ahead of the patrol as far ahead as visibility and terrain permit. In the jungle or on a completely dark night, this may be a very. short distance. On the other hand, good visibility and open terrain may permit and require the point to be 100 meters or more ahead of the patrol.

(2) The point maintains direction by occasional glances at the compass and by maintaining visual contact with the patrol by looking back and orienting on the patrol. If two or more men are used as the point, they maintain visual contact with the man on their right or left.

(3) The point moves right and left, ahead of the patrol, screening the area over which the patrol will pass (fig. 80).

(4) The point provides 8ecurity (is is not a trail breaker) and moves far enough ahead of the patrol to provide this security. Only in unusual circumstances of poor visibility and close terrain will the point be close enough to the patrol to be guided by the compass man.

(5) A technique which allows guod use of personnel is to use a three-man security team for point and compass men. Two men work at point while the third is compass man. On long patrols, the men rotate duties. SECTION II. USE OF RADIOS.

138. Use of Radios.

Radios are used sparingly; proper voice procedure and radio discipline are strictly enforced. The depression and release of the transmission button is sometimes sufficient to relay desired information. When transmitting near the enemy, the hands are cupped over the receiver and a low voice is used.

Figure 80. An example of the movement or the point.

139. Infiltration and Exfiltration.

a. There may be times when the enemy situation prevents a patrol from entering or leaving he enemy area as a unit; however, pairs or small groups may be able to sneak into or out of the area without being detected. Movement into an enemy area by this method is called infiltration. Movement out of an enemy area by this method is called exfiltration.

(1) Infiltration.

The patrol splits up as it leaves the friendly area or at a later specified time. Small groups infiltrate at varying times, each using a different route. After slipping into the enemy area, the groups assemble at a predetermined location called the rendezvous point. The rendezvous point must be free of enemy, provide concealment, and be easily recognizable. An alternate rendezvous point is selected in case the initial one cannot be used. If all members of the patrol have not reached the rendezvous point within a reasonable period, the senior man present determines actions to be taken.

(2) Exfiltration.

The same procedure is followed to return to the friendly area. The patrol splits up and returns, reassembling near or within the friendly area.

b. Movement by infiltration or exfiltration breaks up the tactical integrity of a patrol and is used only when movement as a patrol is not feasible.

140. Patrol Bases.

When a patrol is required to halt for an extended period in au area 1:ot protected by friendly troops, active and passive measures must be taken to provide maximum security while the patrol is in such a vulnerable situation. The most effective means of insuring maximum security is to move the patrol into an assembly area, which hy its location and nature provides passive security from enemy detection. Such an assembly area is termed a pat1'ol base (chp 23).

141. Reporting.

Information obtained by a patrol is reported as promptly and completely as the situation and communications facilities permit. Prompt reporting may enable a patrol to perform additional valuable services. For example, a small reconnaissance patrol reports its findings while still near the objective; the commander receiving the report orders the patrol to adjust artillery fire which destroys or severely damages the objective. In this case, two important missions have been executed without the necessity for dispatching a second patrol. In other instances, the prompt reporting of information may enable the commander to dispatch troops to engage targets that might otherwise escape.